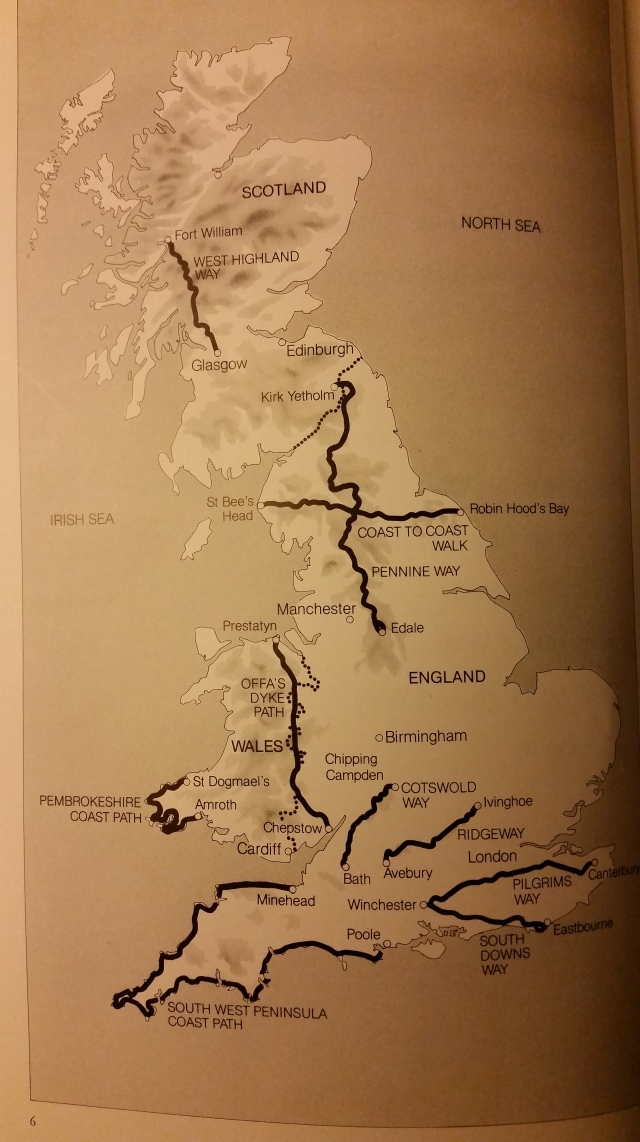

Not long ago I was browsing a small used book shop in a little town about an hour north of Little Rock, Arkansas, when I was delighted to find, ironically and serendipitously, I believe, The National Trust Book of Long Walks in England, Scotland, and Wales, published in 1981, written by Adam Nicholson with over 200 color and black and white photographs. The book describes over 10 long walks, all of them over 80 miles, with the longest over 500. A couple of the walks follow the rugged coastlines of Wales and Southwest England; a few follow the hilly downs of Southern England; Offa’s Dyke Path is built on or follows the earthwork, constructed in the eighth century, that marked the border between England and Wales; one path runs down the Highlands of Scotland; and one path allows the walker to cross England from coast to coast, from St. Bee’s Head to Robin Hood’s Bay.

According to the author, “a fifth of the British population now go for a walk of several miles at least once a week” (7), and apparently, walking is still quite popular in Britain. According to their website, “the Ramblers is a charity whose goal is to protect the ability of people to enjoy the sense of freedom and benefits that come from being outdoors on foot. We’re an association of people and groups who come together to both enjoy walking and other outdoor pursuits and also to ensure that we protect and expand the infrastructure and places people go walking.” Among other things, the organization was instrumental in the passing of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000, which helped to protect the “Right to Roam” (jus spatiandi in Latin) in certain uncultivated and common lands in England and Wales. The group works to maintain relationships with landowners, maintain pathways, fight for access to coastal and undeveloped areas, and promote walking for people of all ages.

I love the idea of rambling, which for me, suggests more than walking an established trail that takes you from point A to B. It suggests wandering with no certain destination, no prescribed path, to go where fancy and whim takes me. As Nicholson says,

“each of these walks becomes a personal adventure, full of personal discovery. That is the pleasure of walking: the abandonment of all vehicles and the dropping of any kind of barrier between you and the landscape. You are on your own and the geology, geography, and history of this island all become tangible; you get to know them through the soles of your feet. The differences between limestone and gritstone—one producing endless carpets of turf, the other peaty mud, which in Lancashire is called ‘slutch’; between beaches made of the liquid sand of sedimentary rocks and of the large-grained gritty sand of igneous rocks; between the level backs of chalk downs and the deeply dissected nature of hills made of less pervious rock; between the unenclosed heights of Welsh mountains and the carefully divided slopes of all but the highest Pennines; between the settlement patterns of the Celtic and the Saxon lands—all these deep geographical and historical structures have an effect on . . . the walker’s life. . . . To go for a walk is to enter into and subject oneself to the physical conditions and processes which have dictated the lives and actions of men in various parts of Britain. There is no better way of getting a sense both of the degree to which human beings have moulded our landscape and at the same time of how superficial and temporary that apparently massive contribution is. It is an elaboration merely of a surface which is shaped by two giant forces—the weather above, and the deep slow movements of volcanic and mountain-making energies below. At any one moment the look of the earth is the product of those two powers, one reducing, one elevating, each acting on the other.” (7-8)

Coming from the United States, where we drive our cars to any destination more than a couple hundred yards, the idea of so many people rambling pleases me. In the Southern United States where I live, where the majority of land is privately held and access protected under threat of penalties and even violence, the ability to ramble in woods or fields or mountains usually requires the commitment of a car journey to a remote national forest or state park.

Nicholson’s book is heavy—no field guide here, but rather is something to settle down with on a cold winter evening and plan the next adventure. The book is out of print, and perhaps could bear updating, but that’s what the internet is for. The book, which can be found quite cheaply and easily online, deserves to be set on the bedside table and returned to over and over. It expresses a love for the land forms, geology, plants, animals, history, and the people of Great Britain. He doesn’t just tell a walker how to get from Point A to Point B. He describes the walks in a narrative style that makes the reader a companion. For Nicholson, walking is more than a bucket list, but something to be savored.

It is with this spirit that Nicholson closes the introduction by quoting the American poet Denise Levertov:

Let’s go—much as that dog goes,

intently haphazard. . . .

Under his feet

rocks and mud, his imagination, sniffing,

engaged in its perceptions—dancing

edgeways, there’s nothing

the dog disdains on his way,

nevertheless he keeps moving, changing

pace and approach but

not direction—‘every step an arrival’. (qtd. 9)